In large technical programs, it’s possible for everything to look fine - and still be going wrong.

An OKR can stay Green for weeks while the underlying work keeps getting fuzzier, slower, and more expensive. By the time anyone questions the value, the program has too much momentum to stop.

This usually isn’t an execution problem. It’s a validation problem.

Where OKRs Start to Drift

Most prioritization frameworks do the right thing at the start. Estimate the impact, size the effort, and agree the investment makes sense. The bet is simple: the impact will justify the effort.

RICE is one example of this, but the pattern is broader than any single framework. We calculate ROI once, lock it in, and then move on to delivery.

What changes is everything underneath.

As work progresses, hidden complexity shows up. Dependencies take longer than expected. Operational load eats into capacity. Reach assumptions quietly weaken. None of this looks dramatic in isolation, but together it changes the cost profile of the work.

At that point, the project may still be shipping - but it’s no longer the investment we thought it was.

Most status reporting doesn’t surface this, because it’s designed to track delivery progress, not to revalidate whether the original bet still makes sense.

Planning Is Not the Problem. Freezing It Is.

The issue isn’t that teams plan incorrectly. It’s that plans are treated as static even when execution reality keeps moving.

Dynamic validation treats the original prioritization as a hypothesis, not a fact. As delivery unfolds, it keeps asking a simple question:

Given what we now know, does this work still justify its cost?

This isn’t about re-prioritizing every sprint or re-estimating everything from scratch. It’s about checking whether the assumptions behind an OKR still hold under real delivery conditions.

Two Different Kinds of Confidence (That Often Get Blended Together)

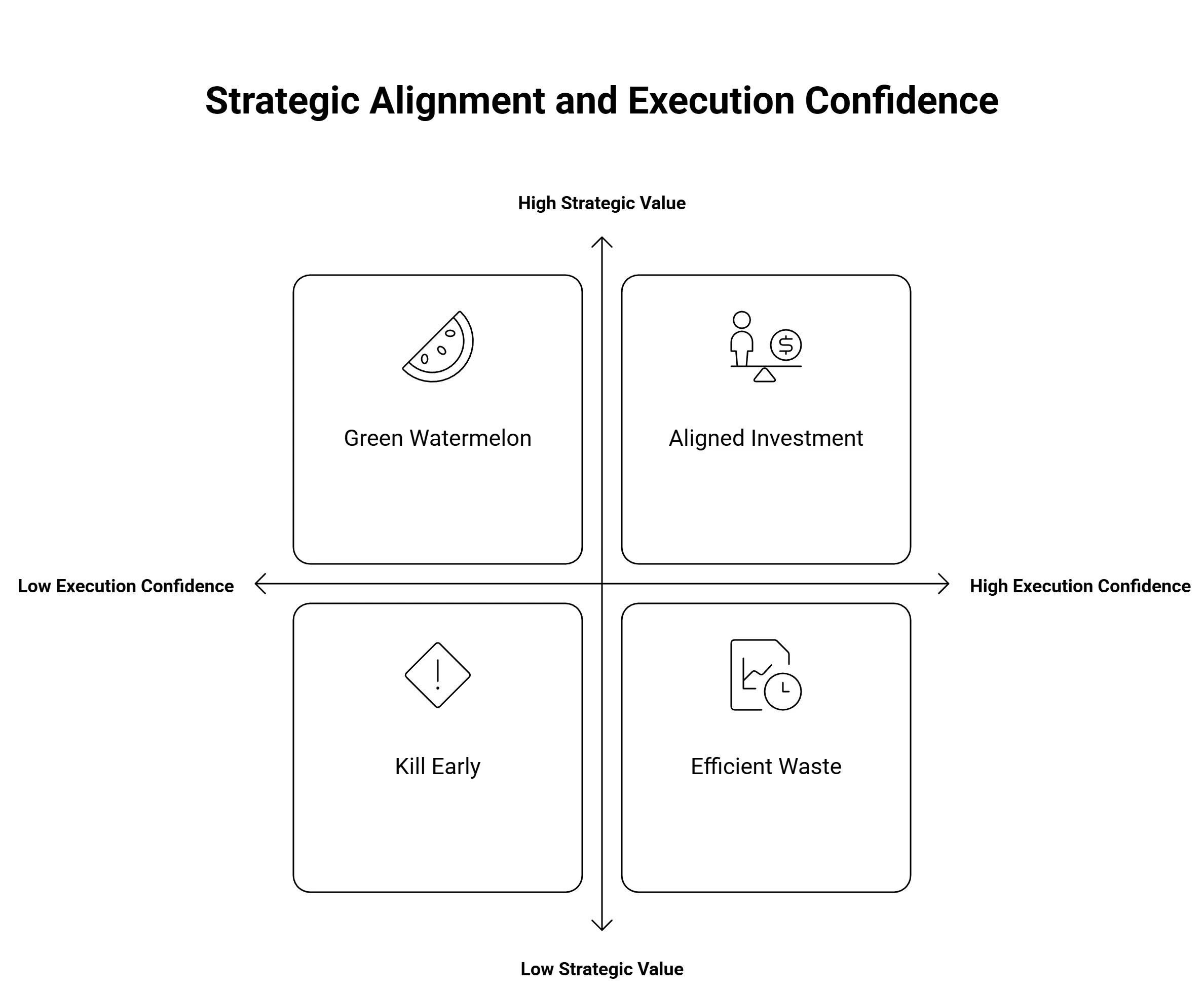

One reason this drift goes unnoticed is that we collapse two different ideas into a single notion of confidence.

-

Strategic confidence answers why: the belief that this work will move a business metric. This is a leadership bet.

-

Execution confidence answers how: the probability that the system design and delivery reality can support that bet.

Both matter. But when they’re treated as the same thing, momentum takes over. Programs stay green because they’re busy, not because they’re still valuable.

How Value Actually Erodes During Execution

In practice, teams don’t need perfect data to spot trouble. Certain patterns show up repeatedly when an OKR starts drifting away from its original ROI.

1. Unbounded work (scope fog)

When large parts of the roadmap remain undefined, timelines become optimistic by default. Progress looks real, but execution confidence is already capped.

2. Capacity tax (hidden work) Incidents, bugs, and operational load quietly reduce available capacity. When this becomes sustained, the original effort assumptions no longer apply.

3. Delivery inventory (dependency drag) Work that’s done but not live accumulates risk. The longer it waits on integration or approvals, the more value it sheds.

4. Effort concentration (diminishing returns) When a single item keeps absorbing more time than expected, it’s not just a delay. It’s a signal that the cost curve has changed.

None of these signals are precise. That’s fine. They are early warnings. Their value is that they show up early.

Why This Doesn’t Turn Into Automation Theater

These signals aren’t meant to drive automatic decisions. They’re meant to trigger conversations sooner - before sunk cost bias takes over.

They’re also imperfect by design. Some work happens off-ticket. Some effort gets misclassified. This only works in teams that are reasonably transparent and aligned on definitions.

Dynamic validation doesn’t remove judgment. It moves judgment earlier, when it’s still cheap. And judgement cannot remove - human factor.

The Decision That Actually Matters

Once effort balloons or capacity erodes, the economics of the work have changed. At that point, leadership has to decide what to do with the remaining budget.

There are only a few real options:

Continue knowingly, because the impact still justifies the cost.

Pause and refactor by paying down reliability or dependency debt.

Kill the work early and redirect the investment.

A healthy OKR isn’t one that keeps shipping. It’s one that still makes sense to ship.

Execution without validation doesn’t fail loudly. It drifts—quietly, efficiently, and on schedule.